My parents came to America and settled in Pennsylvania in the wave of German immigration fleeing the economic and political uncertainty of the first half of the 19th century.

My father and mother were German immigrants. My father Leopold Stoeckel was born in 1821 in Baden, along the east bank of the Rhine River, an area that includes the Black Forest. Perhaps that is where I get my love of the forest, of wood, and making furniture. My parents met and married in Pennsylvania. My father being 18 years older than my mother, I suppose that a cause for their separation that would happen when I was 12 years of age. By that time, my mother had born 11 children, and my parents had moved to the Ohio Territory where they farmed 40 acres near Osceola. Like early settlers we lived in a log cabin and my father struggled to raise wheat and provide for his family. My father supplemented our meager earnings as stonemason, and I too took up this trade, earning my journeyman’s license by the age of 12. This became a matter of necessity for my father’s farm failed and he left the family.

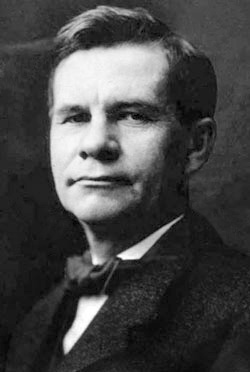

My mother had the good sense to move the family back to Brandt, Pennsylvania where, at the age of 17, I worked in my uncle’s chair factory. His name was Jacob Schlager, and he along with his business partner Henry Brandt, were quite the entrepreneurs. This was my introduction to furniture making. In 1883, after 8 year, along with brothers Charles and Albert, we formed the Stickley Brothers & Company, the same year that I married Eda Ann Simmons. First ventures do not always succeed. My brothers and I parted ways, and I then formed a partnership with Elgin Simonds, a furniture salesman from Binghamton, New York. This partnership had the advantage of creating sales for the furniture I made, and it caused me to move to Upstate New York which was closer to the clients who bought my furniture.

Syracuse would eventually be my home.

By the year 1888, I turned 30 and my wife Eda and I were the parents of two small children. Simonds and I were achieving some success in Syracuse. I dabbled in real estate, tinkered with machines like a better wood-bending machine and a belt sander, securing patents in both the United States and Canada.

In 1895, my wife and I made our first trip to Europe where I was introduced to the ideas of William Morris and John Ruskin. They too had seen the effects of a rising industrial age and became concerned with its effects on the working man. Amid the pomp of ceremony of the Victorian Age, the world seemed to have forgotten the artistry of the craftsman and the value of his labor. An Arts & Crafts Movement had taken hold in England, and I wanted to be its American proponent.

It was 1898, I turned 40, my wife and I had a large, well-appointed home in Syracuse which accommodated the six children we now had. But I was restless. Simonds and I parted ways, and I experimented with the idea of making furniture in the manner of true craftsmen, honestly and simply.

The new century was the perfect opportunity to introduce my New Furniture. In the eyes of some it was plain, but that was the point. The design highlighted the beauty of the wood and the quality of the construction. This was not intended to be ornamental furniture, but furniture that served a purpose, enduring furniture that would last for generations. To help me with design, I brought in Henry Wilkinson and LaMont A. Warner. I changed the name of my company to United Crafts and within a year started a magazine called The Craftsman with Irene Sargent as editor.

Our magazine became the proponent of a new lifestyle, one that accommodated the working class, middle America, and the craftsman style homes that were popping up across the country like prairie flowers. Our furniture designs continued to emphasize mortise and tenon joinery and the workman’s pride in the structural qualities of his works. Hammered metal hardware, armor-bright polished iron or patinated copper also emphasized the handmade qualities of the furniture.

In May of 1903 I hired architect Harvey Ellis who died less than a year later, but still influenced the company going forward with his lighter pieces and inlay designs. Ellis’ artistry was reminiscent of Scottish designer Charles Rennie Mackintosh, but uniquely his own.

My brothers Leopold, Albert, Charles, and John George also produced Arts and Crafts furniture, and we collaborated and worked together in varying ways over the decades that followed.

The Lord’s Word sustains me in all that I have faced. And in the curse of the Garden of Eden I find a blessing. For “in the sweat of thy face, shall thy eat bread,” Genesis 3:19.

The Flemish motto I adopted, Als Ik Kan, is still my mantra. I have worked to the best of my ability. That I have failed on occasion is not a source of disappointment. What is life, if not to strive, to achieve, sometimes to fail and by failing to learn and improve. This I know – All the romance in the growth of civilization is born of conflict. Heroes are not made of affluence, ease. Adversity is their birthright, difficulty their means to opportunity.*

I believe that in some small measure I have made life better for the working man, for the middle class, and for America. I believe that the future is bright with hope.

The sun has risen and set many times over the course of my lifetime.

An old man often returns to his childhood and his memories, to his beginnings to get a bearing on his accomplishments. I think back on the little log cabin my father built in the woods of Ohio. I still admire the forests of sturdy oaks and the groves of stately walnut. From these stands of wood, my father built our house. There are elements of intrinsic beauty in the simplification of a house built of logs. First, there is the bare beauty of the logs themselves with their long lines and firm curves. Then there is the open charm felt of the structural features which are not hidden under plaster and ornament, but are clearly revealed, a charm felt in Japanese architecture. The quiet rhythmic monotone of the wall of logs fills one with the rustic peace of a secluded nook in the woods.

* The sources are many. Gustav’s thoughts were published in The Craftsman Magazine, in the editorial articles titled, “Als I Kan”. Much of these personal observations come from his editorial in The Craftsman Magazine, dated November 1911.